Roadmapping as process

It is often said that "the process of roadmapping is more important than the roadmap itself", as useful as roadmaps are for supporting strategic understanding, communication and alignment. This is attributed to the consensus building nature of the process when used to mediate strategic dialogue, often in the form of workshops. Consensus, while beneficial, brings with it some risks, so a healthy strategy should be subject to challenge. For example, Motorola in their original 1987 technology roadmapping approach required a 'minority report' to be submitted along with roadmaps developed through a consensus building process.

How to balance and blend human and digital in such processes is an interesting question. It's clear there is a spectrum of options, with successful deployments observed at both extremes, and between, and that digital technologies and applications continue to develop rapidly.

Roadmapping used to guide strategic dialogue in a multi-divisional corporate innovation workshop, with participants empowered with paper, pens & post-it notes

How long does it take to develop a good roadmap? Between 2 hours and 2 years, it has been observed - it depends on how clear your strategy is. A pair of scissors and some glue are quite useful if presented with a glossy and substantial strategy document - if the strategic plan is complete and coherent, it should not take long to create a roadmap to accompany it.

Roadmapping

It's not a good idea to confuse your roadmapping process with your strategy or innovation management process (or any other process for that matter), which it is prone to be due to its visible integrative nature. Roadmapping supports these other business processes; it has limited impact by itself. The unique distinguishing feature of roadmapping is the use of structured visual representations as a primary management lens, and its role is best understood through this perspective. The core principles of roadmapping are simple, which is helpful for dealing with complex business and system challenges. A single tool alone is limiting, and so a toolkit approach is advocated.

As an executive from Philips was heard to say "roadmaps are dirty mirrors", meaning they will reveal the good, the bad and the ugly. This makes roadmapping a useful diagnostic, especially the first iteration, with a need to moderate expectations if the process reveals problems that have to be dealt with before a satisfactory roadmap can be developed. Don't blame the messenger - roadmapping, or brush the problems back under the carpet. "If you can't see it, you can't manage it" - as a structured visual approach roadmapping can help.

Implementation

To be effective roadmapping must align with and support other key business processes and tools, together with the associated information flows, aligning stakeholder perspectives, decision making and resource allocation. Roadmapping in isolation has little value, and the approach is best considered as a service, as illustrated in Fig (a) below, aligned with key review and decision points in the client process, represented as a ‘funnel’. At earlier ‘front-end’ stages the process will be very exploratory (‘sandbox’ mode), with iterations rapid and information volatile. As the quality of the roadmap and information contained in it increases, to the point where it provides useful motivation and evidence for investment decisions, processes will generally be more formally managed, and roadmaps curated.

Fig (b) above highlights various process elements that will influence the development of a roadmap, and it is possible to overlay any process logic on the roadmap canvas. This might be based on market pull, starting at the top and moving down the roadmap layers, or technology push, starting at the bottom and moving up, or any other logic. Fig (b) provides a balanced process logic, focusing on the centre of the roadmap, approached from top and bottom (opportunities & threats, strengths and weaknesses - i.e. SWOT), and from the right and left (vision led, recognising legacy and path dependency). A template representing this logic is available here .

In the Philips’ process illustrated below, roadmap creation is a distinct process step within their overall innovation process, which gives weight to both market and technology considerations, integrating information into a coherent strategic plan. However, there is merit in utilising the structures and taxonomies associated with roadmapping throughout such processes, to improve communication, information flows and integration of tools. Thus, boundaries of roadmapping are not always clearcut, given its integrative functionality in management toolkits, with it possible to overlay the entire Philips process on the roadmap canvas.

Roadmapping in Philips’ innovation process (EIRMA, 1997)

Workshops and other consultative interventions are common elements of roadmapping processes, as illustrated below. Of course, the situation in reality is much more complex in large organisations, and a substantial process mapping activity may be required to understand knowledge and information flows. Key success factors from a study of foresight (sector) roadmapping applications (De Laat & McKibbin, 2003) are highlighted in red, which are also useful for firm level applications.

Roadmapping is a subservient management process that uses roadmap architectures as the primary lens, supporting strategy, innovation and other business processes

Starting up a roadmapping process / system is different to sustaining it, which is notoriously challenging. The limiting factor is the underlying strategic coherence in the organisation and its management and business systems, rather than the roadmapping method itself. Roadmapping is rather simple in nature, and can help to address the complex situations that arise in organisations over time. "Think big, act small" is a good way to start, with it generally making sense to initially focus on the human process, beginning with a meeting and/or workshop to scope the initiative, test the tool and address a strategic problem of concern or as a diagnostic. Aim to deliver early benefits and understanding of how the method can help, how it should be configured, and to agree the way forward. White boards, paper, post-it notes and pens are a good starting point, progressing to more sophisticated systems as appropriate.

Gerdsri et al (2009) have developed a change management framework to support implementation, breaking down the process into three stages: Initiation, Development and Integration. Building on this, Hirose et al. (2020) have proposed a maturity framework (see below), as means to calibrate performance and identify actions to improve capability, aided by the ‘roadmapping roadmapping’ template available here.

Process mapping activity, to clarify how roadmapping fits in with other management processes and systems

Technological innovation

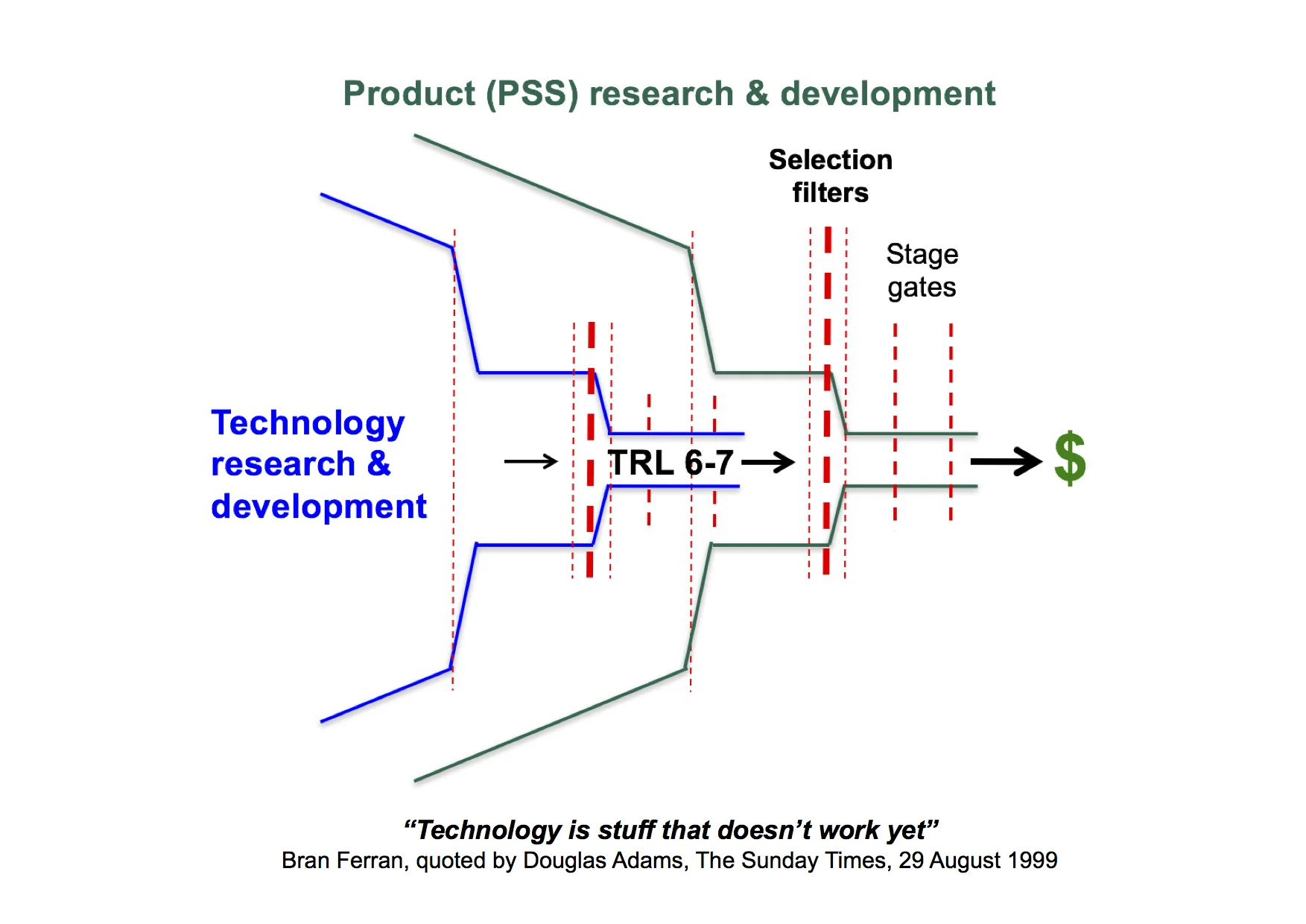

Technology-intensive innovation poses particular challenges that are often overlooked in standard product and service innovation literature and teaching programmes. Technological invention and innovation is uncertain and risky, and can take a long time - it is unwise to rely on unproven technology for a product development if time and cost targets are critical. Similar management frameworks can be applied to both product and technology development - for example, the innovation 'funnel' and Cooper's stage-gate frameworks, used with NASA's technology readiness levels (TRLs) to assess technological progress and align the two development processes. The layered structure of roadmaps helps to distinguish between and synchronise research and development projects with product releases, upgrades and commercial milestones, and also different technology development clock speeds (e.g. software vs hardware).

'Double funnel' for technology-intensive innovation, using technology readiness levels (TRLs) to align product-service-system (PSS) and technology development processes.

'Fast-start' workshop methods

Cambridge 'S-Plan' and 'T-Plan' 'fast-start' workshop methods are designed to efficiently support the initiation of roadmapping in organisations of all types, as reference processes to adapt from. They can also be used to support review and renewal of existing roadmapping initiatives. Workshop methods are designed to be modular, flexible and scalable, enabling toolkit configuration and deployment.

Methods are based on generic frameworks that can be readily adapted to context in terms of process and structure. The underlying roadmap architecture is neutral to process, which can be overlaid on the roadmap canvas. Process prompts can be embedded into workshop templates to support utility, as demonstrated here.

Light-touch 'fast-start' methods were initially developed for application in small organisations, as there was a perception in the late 1990s that technology roadmapping was the preserve of large technology firms. This is not the case at all, although of course a small start-up will need a very different solution to an established multinational. An impressive long-running national (Singaporean) SME initiative has been reported by Holmes and Ferrill (2005), adapted from the T-Plan approach, with training provided to support transfer of the approach.

Efficiency is also valued by larger firms, particularly when trialling a new method. Roadmapping can always be expanded as required, as it is integrated into management systems, at business, corporate, sector or national levels. Two diverse examples of large corporate applications are provided below - both multinational first-tier suppliers of similar scale (annual revenues of about $10B), in very different sectors.

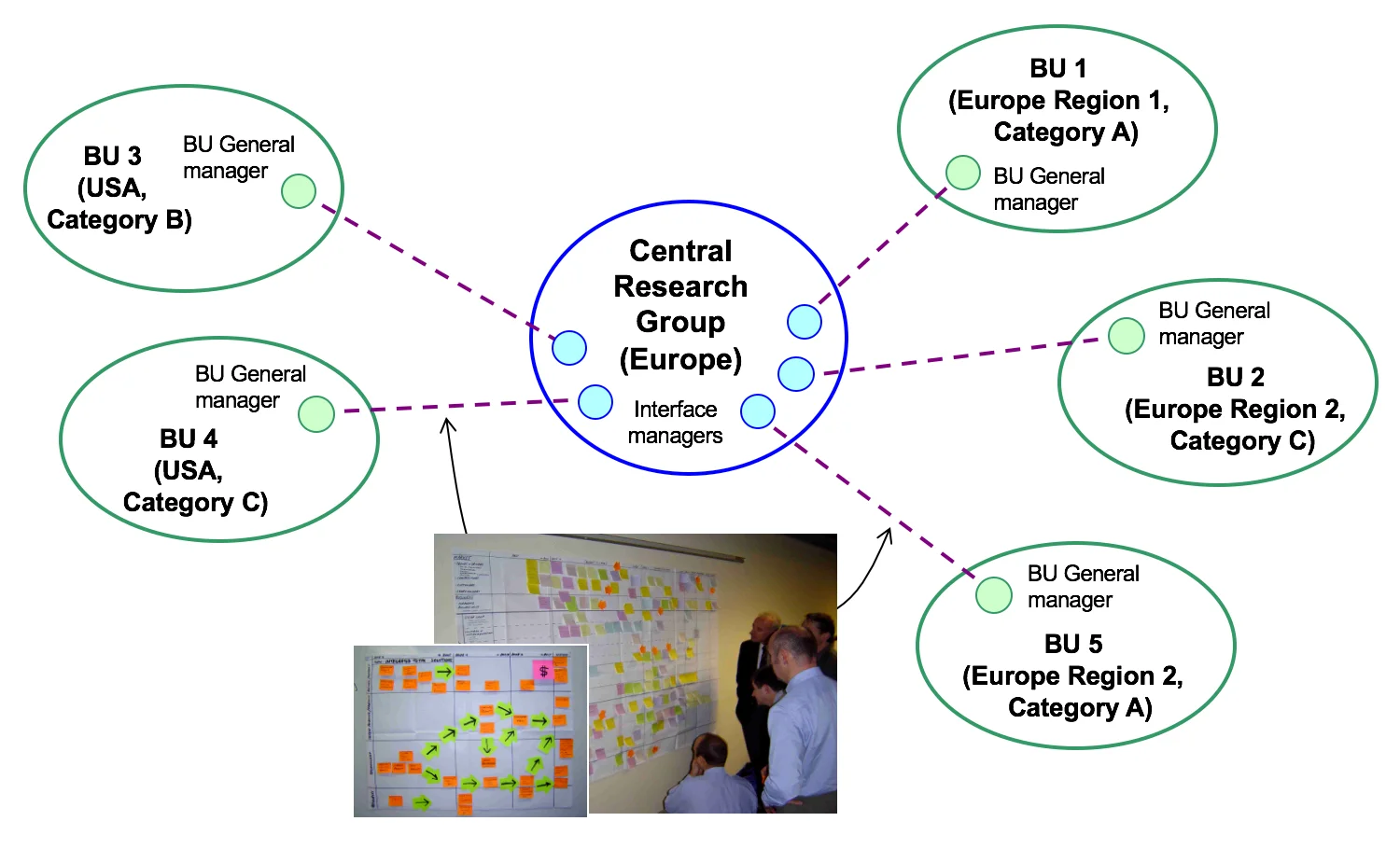

a) Sequential roadmapping application, with refinements as process progressed, with the purpose of aligning corporate research with commercial business unit needs, and transferring the method to the company. Following the first pilot, a series of roadmaps were produced collaboratively by teams from the central R&D facility and diverse business units in terms of geography and market segmentation. Each workshop lasted 1.5 days, involving 20-30 participants from technical and commercial functions, with senior involvement and endorsement. With a common roadmap architecture it was possible to spot some key synergies early, with the full picture emerging over time, with a formal review after a year. The technology portfolio was revised substantially to be more business focused, aligned with roadmaps, with a proportion of the portfolio reserved for longer term more speculative R&D. A carefully selected pilot is a low risk starting point in such initiatives, demonstrating early benefits.

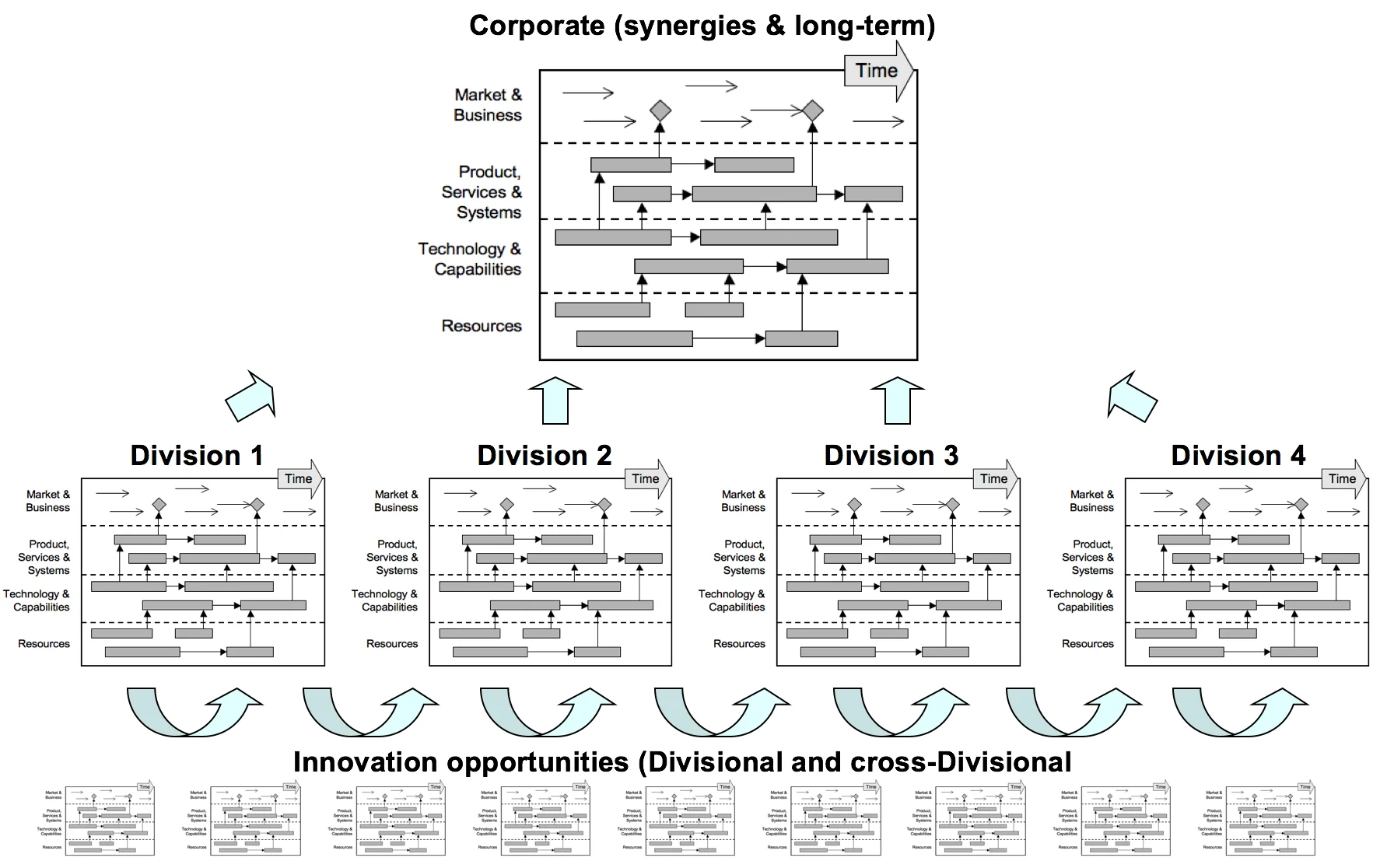

b) 'Big-bang' parallel conference-style corporate roadmapping application, preceded by business unit trials to demonstrate the approach. The aim was to identify and explore innovation opportunities within and across divisions, producing a coherent family of roadmaps. The workshop ran for 1.5 days with a team of 8 facilitators - 2 per Division, each including a staff member to learn the process. The global event was attended by 65 participants representing a mix of technical and commercial functions, three months in advance of a corporate strategy cycle deadline. A separate radical ('horizon 3') innovation process was subsequently held, to ensure a balanced portfolio and to manage long term opportunity and risk. At least one substantial new business unit emerged from the cross-divisional focus enabled by the process.

It is helpful to include all relevant stakeholder groups in workshops - particularly technical and commercial, and possibly strategic customers and suppliers. This can lead to large numbers of participants and facilitation challenges, with methods needing to adapt to group size and task, as illustrated below. The 'self-facilitating' templates for small groups are designed to empower users, improve process efficiency and effectiveness, and to relieve the burden on facilitators, freeing up time to focus on higher value support activities. Medium-sized groups require engaged facilitator attention, whilst large groups demand a more orchestrated approach.

Workshops are scalable, with facilitation techniques adjusted to group size

At the other end of the scale, roadmapping is a useful framework for personal reflection, to organise strategic thoughts. And as a research tool - retrospectively, useful for longitudinal case studies, to learn from the past. For example, mapping innovation projects, or mergers & acquisitions. Roadmapping provides a useful design and planning framework for facilitator and key stakeholders, to clarify focus and scope ('the exam question'), and to gather data and organisational information.

The kind of human-centric highly interactive workshop methods described above can be emulated online via digital whiteboard platforms, such as Miro, Mural and iObeya, although the process should be adapted to suit the medium. For example, a one-day intensive physical workshop is better disaggregated into a series of shorter modules spread over a period of days. There are advantages and disadvantages associated with physical vs digital solutions, and if some co-location is possible a blend of the two might be appropriate. It is possible to use large touch screen displays to replace physical paper processes for a fully digital solution that does not lose the benefits of face-to-face interaction.

Experiment comparing paper vs digital workshop processes (Source: Prof Maicon Oliveira)

Roadmapping, as with other such approaches, must usually be adapted to fit the specific context, with implementation within a business unit taking some time - up to a year or two is not uncommon. Corporate deployment is even more challenging (as described by Cosner et al., 2007), and rarely observed for reasons not of the tool's making, but rather due to the general challenges of deploying any coherent strategy process in a complex, dynamic and political environment. For these reasons it is not uncommon to find pockets of successful roadmapping in organisations, often unconnected, focusing on parts of the system that managers can influence.

Roadmapping is an ideal tool for senior managers concerned with strategic alignment, from the board level down. However, as it is very seldom included in standard business textbooks and teaching programmes, many of those who would benefit most from the approach know little about it. This omission is one motivation for this website, to provide information and support that is unlikely to be available from your local business school.

Definition of ‘roadmapping’

Building on the discussion above, the following general definition has been provided by Kerr & Phaal (2022), which is considered to encompass the key features of roadmapping, incorporating key aspects of the definition of ‘roadmap, provided at the end of this page (“a structured visual chronology of strategic intent”).

Roadmapping is “the application of a temporal–spatial structured strategic lens”

This definition avoids the trap of simply defining roadmapping as the process of developing roadmaps. This can be readily discounted, as roadmapping can be used in a problem-solving or diagnostic mode, or as architectural support within strategy and innovation processes, without the intention of developing actual roadmaps. The governing framework for roadmapping shown in the figure below is very flexible and powerful for organising the data, information and knowledge involved in such processes, to address the various fundamental questions associated with roadmap structure.

Governing roadmapping framework (Kerr & Phaal, 2021)

Other perspectives

If you have any queries regarding research, training, collaboration or other support please contact me at rob.phaal@eng.cam.ac.uk.